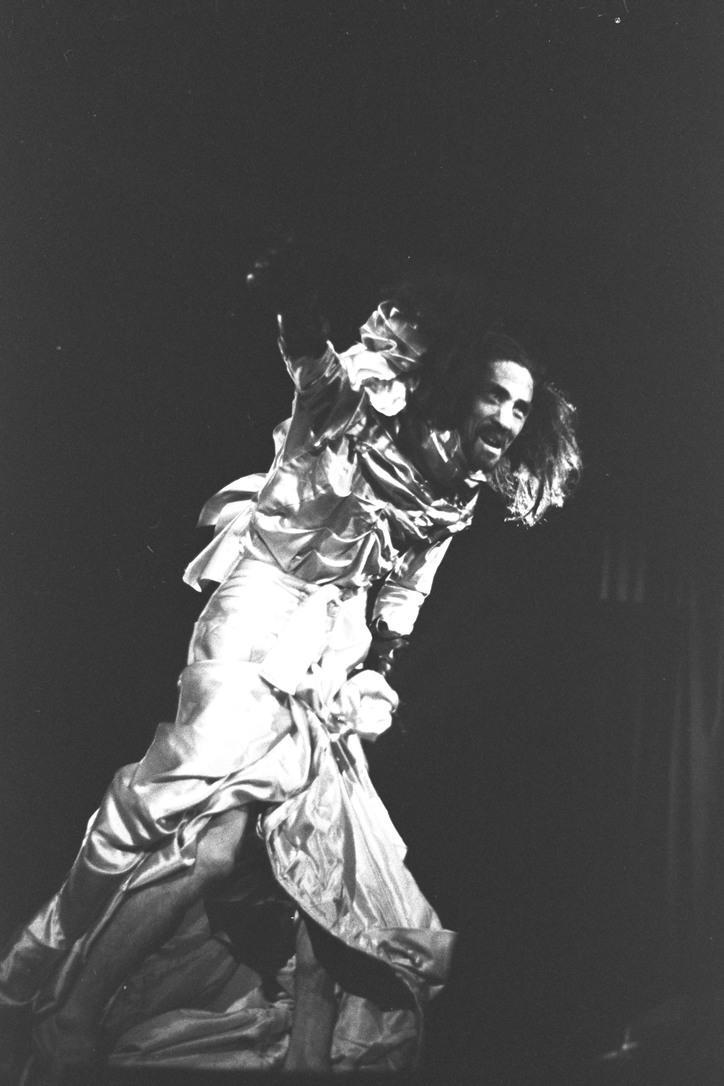

The second work of the program, Butoh Beethoven, in complete contrast to the first piece, embodied an extroverted, impulsive, aggressive energy. Draped in a full length black robe, Vangeline stands on a dark mound surrounded by a circle of lit, white pebbles.

She holds in her hand a red, flashing light that she manipulates for strobe effect against her jerky, writhing torso – all to the sounds of air raid sirens and bombers.

After this overture, she squats to the ground, extinguishes the red strobe light, and in the darkness picks up a conductor’s baton. The baton lights up like a magic wand as we hear the sound of an orchestra tuning. The illuminated baton appears to float upward as the dancer’s body is invisible on the unlit stage.

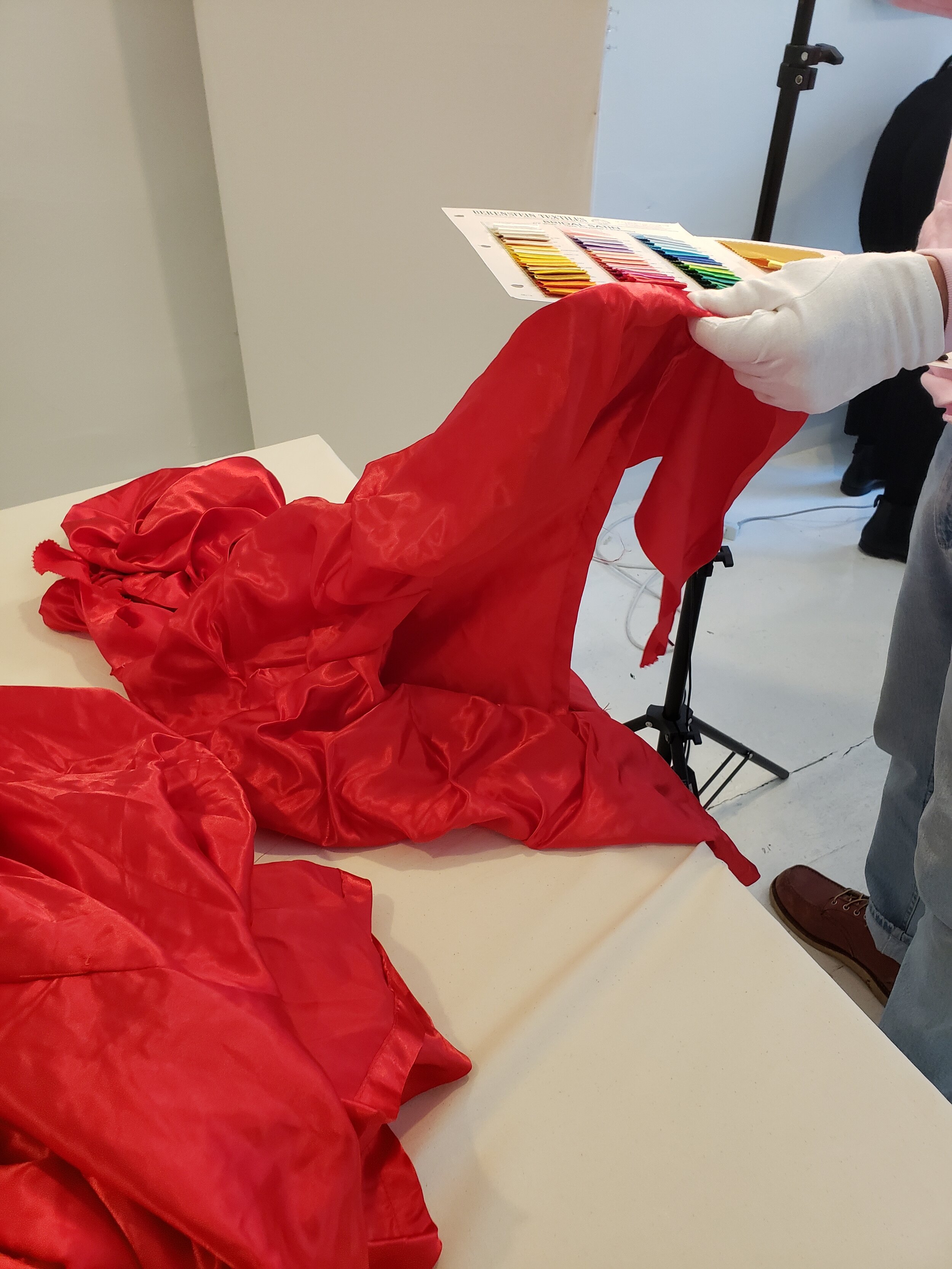

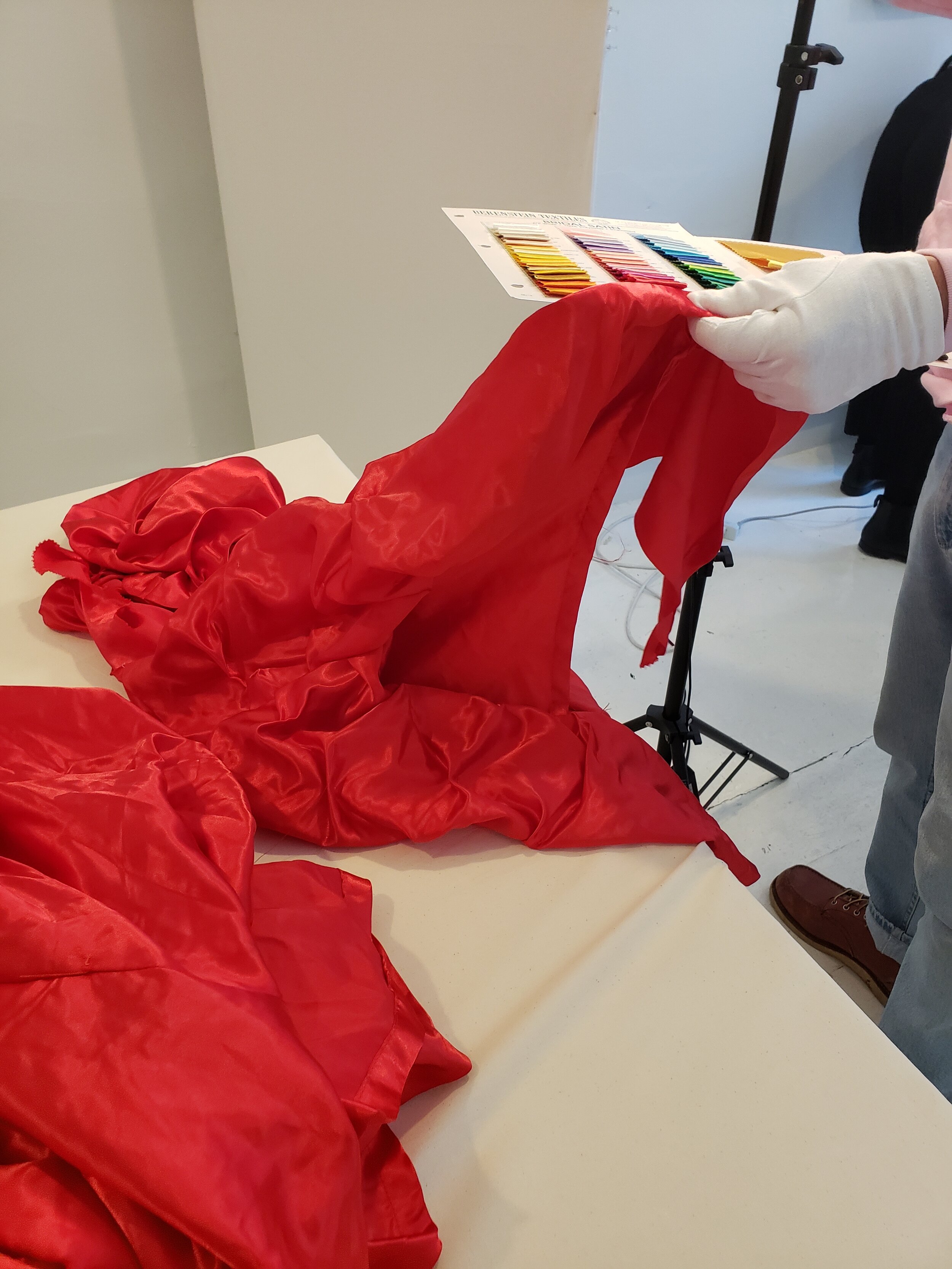

When the stage lights do come up, Vangeline sheds her black robe to reveal a long white

dress composed of tiers of handkerchiefs designed by Todd Thomas.

She launches into an impassioned fit of conducting Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony – hair

and dress whipping and flying about, white powdered face contorting in grotesque expressions.

Her arms churn up the music’s majesty as she appears to draw the powerful sounds, at times from the earth and then from the heavens. She descends to the ground in a state of internal process as her contorting face takes on the appearance of a ghoulish mask. She extends a trembling, clawlike hand as a loud drone drowns out the symphony.

Is this the torment of the master of sublime sound going deaf? From this morbid scene, Vangeline

(Beethoven) recovers to the sound of planes hovering over crashing waves. Then, only crashing waves are audible as she drifts backward into unlit darkness.

And once again, as if to embark on another act of creative genius, she illuminates the conductor’s

baton and stretches her arm upward.

Who was this French-American young woman – a dancer who was most likely shaped in the styles and technique of the West? What inspired her to become an exponent of butoh? Shortly after the performance, I sat down with Vangeline to discuss this and more. She had been trained in ballet and jazz and was working as a jazz dancer in 1999 when she saw Sankai Juku (internationally known butoh troupe founded in 1975 by Ushio Amagatsu) perform at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

“I fell in love. So, I started looking for a butoh teacher,” she disclosed. She had felt limited by the sexualized roles she was cast in as a woman in Western dance and was looking to explore beyond that. The decision to perform her own work came hand-in-hand with embarking on butoh training. At first she labeled her choreography “butoh-influenced.”

After five years and a thorough review of her work, her Japanese mentors gave her the permission

and encouragement to use the white face paint that is a hallmark of the form and to call her work “butoh.” She has now studied for eighteen years with butoh masters in Mexico, the United States, and Japan. Her primary teacher is Tetsuro Fukuhara, a sixty-eight-year-old, second generation butoh artist with whom she collaborates on projects and events with the goal of making butoh accessible to the general public.

Vangeline emphasized, “Butoh masters of the second generation are passing. We are navigating

the challenge of preserving a rich legacy, but also giving space for new work and evolution.”

One of the new areas Vangeline doggedly pursues is the use of butoh in prisons. She explained

that she had always felt an affinity for imprisoned populations and remarked, “I have often thought that not having dominion over your body is a kind of death.” Early on while teaching butoh classes, she recognized the potential of the form. Indeed, the intense concentration on body awareness honed through butoh training makes it a particularly transformative practice for incarcerated populations.

For three years, her proposals were rejected by the New York Department of Corrections. Finally, after calling herself a “modern dancer,” they offered her a trial opportunity to work with a female population. After three months, the administration recognized its value and bought into it.

She explained, “Correctional facilities are very noisy places. There is no privacy and people are always measuring and evaluating each other. Butoh gives the participants the quiet space to concentrate on awareness of their own bodies and emotions. This translates into less

anxiety, more receptivity, and more accomplishment.”

But this is not a one-way street.

Vangeline sees the prison work as a natural extension of butoh’s investigation of the unconscious. She asserted, “Prisons are the part of society that we don’t really look at or acknowledge. They are part of the uncomfortable, taboo material that Butoh examines.”

I questioned Vangeline about the relationship between the two performance pieces. She sometimes dances them in reverse order. She replied, “They are two sides of the same coin – one is feminine; one is masculine. One is the moon; one is the sun.” She confessed that switching from one to the other is difficult either way, although, she is finding it easier to make the transition from the slow, controlled, minimal movements of Eclipse to the expansive energy of Beethoven as opposed to the other way around.

Not surprising, Vangeline admits to having a gripping fascination with things that glow in the dark and the body’s reaction to light and darkness. In Eclipse, Vangeline is the source of light. In Beethoven, the creative impulse symbolized by the conductor’s baton is the first and final glint of light. Perhaps one can only discover the light if one truly probes the darkness.

©2018 Karen Greenspan

http://www.balletreview.com/

LINK TO ARTICLE PDF